|

Benedictines, Cistercians,

Trappists, and Carthusians |

|||||

Stanley Roseman

The MONASTIC LIFE

The MONASTIC LIFE

The FOUR MONASTIC ORDERS of the WESTERN CHURCH

© Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis - All Rights Reserved

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

"The third abbot of Cîteaux was an Englishman, Stephen Harding," explains Roseman in writing about the early Cistercians. "Stephen, who was elected abbot in 1109, had accompanied Robert from Molesme and had served as his secretary and sub-prior as well as prior to Robert's successor, Alberic.

Roseman's extensive research and studies on monasticism and the encouragement of monks and nuns whom he came to know through his work led the artist in the 1980's to write a text to accompany his paintings and drawings. The Oxford scholar and Benedictine monk Dom Bernard Green kindly read a draft of Roseman's manuscript and writes in letter to the artist commending him for his text: "You portray the background and aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life.''

5. The music book of 132 pages for the OCSO General Chapter contains the Psalms and hymns for each day's Office of Lauds. The book includes music notations and pages for celebrating the Mass.

6. On the back cover of the music book for the OSCO General Chapter 2011 is reproduced A Trappist Monk entering the Choir. Roseman has created a striking mise-en-page with an expanse of pictorial space. Fluent strokes of the chalks express movement of the figure as the Trappist monk in his voluminous cowl enters the choir for the Divine Office.

The General Chapter

The following are excerpts from Roseman's text where he speaks about the history of the Cistercians:

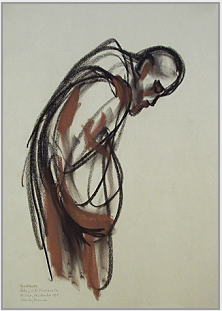

3. Frère Materne in Prayer, 1979

Abbey of Cîteaux, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, France

Abbey of Cîteaux, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, France

Roseman's work at the Abbey of Cîteaux in June 1979 includes Frère Materne in Prayer, a beautiful drawing in bistre and white chalks with touches of black chalk on gray paper, (fig. 3). The drawing conveys an ethereal quality in the fine modeling and interplay of line and tone depicting the elderly, ascetic monk in prayer, his white beard as white as the voluminous cowl that envelops him.

The Beginnings of the Cistercian Order

"To oversee the founding of the Abbey of Clairvaux, St. Stephen sent from Cîteaux a man in his early twenties, Bernard of Fontaine, who was to become a leading churchman of his time. . . .

The Cistercian General Chapter began in the twelfth century and continues through to the present day with the Order of Cistercians of the Common Observance and the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance. On the General Chapter, Roseman writes:

"A twelfth-century Cistercian document called the Charter of Charity (Summa cartae caritatis) set down constitutions for the Cistercian Order. Section IV, titled 'The Annual Chapter of Abbots,' prescribes an annual assembly of abbots at Cîteaux 'to meet one another, to tend to the affairs of the Order, to strengthen the peace and to preserve charity.'[4]

"The General Chapter was an important innovation in monastic organization. Professor C. H. Lawrence states in Medieval Monasticism that the General Chapter 'represented something new, not only in the monastic tradition, but also in the polity of medieval Europe.' The annual General Chapter 'was the only international assembly known to Europe, apart from general councils of the Church, which were extremely rare events.'[5] The Cistercian General Chapter was a forerunner to today's international conventions, whose members gather on a regular basis to discuss a range of topics and concerns.

The cover reproduces Roseman's beautiful drawings A Trappist Monk entering the Choir, Abbey of La Trappe, 1997, (detail, left); and Trappist Monks entering the Choir, Abbey of La Trappe, 1997, (detail, right).

"The concept of the Cistercian General Chapter was later adopted at Cluny and by other Benedictine congregations, as well as by the Carthusians in 1141. Annual General Chapters were introduced into the legislation of other religious institutions, including the Premonstratensians, an order of canons regular, founded in the twelfth century; and the mendicant Order of Friars Minor, or Franciscans; and Order of Friars Preachers, or Dominicans, both founded in the thirteenth century.

Music book for the Office of Lauds and the Mass

General Chapter of the Order of Cistercians

of the Strict Observance, 2011.

General Chapter of the Order of Cistercians

of the Strict Observance, 2011.

The Order of Cistercians of the Common Observance, or Cistercian Order (O.Cist.); and the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, or Trappist Order (O.C.S.O.), share a common heritage dating back to the closing years of the eleventh century.

The Cistercians

and The Trappists

and The Trappists

4. Abbey of Cîteaux

Coat of Arms.

Coat of Arms.

"The General Chapter convened yearly at Cîteaux to coincide with the feast of the Holy Cross on September 14. By the thirteenth century, Cistercian monasteries extended across Europe - from the British Isles to Poland, and from Scandinavia and the Baltic States to the Mediterranean. Consequently, the long, potentially dangerous and expensive journeys for many abbots hindered annual attendance at the General Chapter.

"And like a ship without a captain, it was not in the best interests of a monastery to be without its abbot for as much as several months each year. Concessions therefore were made to allow those abbots from distant monasteries to attend the General Chapter every four or five years, with representatives attending in the intervening years in the abbots' stead.

"At the New Monastery, Novum monasterium, as Cîteaux was then called, the monks shortened the extremely lengthy liturgical worship of the Cluniac monasteries and adhered to a timetable and the number of Psalms for the Divine Office as prescribed in the Rule of St. Benedict. The Rule commends the virtues of work as a complement to prayer. The early Cistercians emphasized the importance of manual labor by which to earn a livelihood, mainly from farming. The monks practiced austerity and self-denial; maintained an abstemious diet; and devoted hours to meditation and private prayer.

"The nascent community changed the traditional Benedictine habit of a black scapular worn over a black tunic to a black scapular worn over a tunic of 'white' or unbleached wool. The monks wore white cowls at the Divine Office in choir. Thus the Cistercians came to be known as the 'White Monks.' "

"The New Monastery gained vocations, and under the abbacy of Stephen Harding, Cîteaux founded the abbeys of La Ferté, 1113; and Pontigny, 1114, both in Burgundy; and Morimond, 1115; and Clairvaux, 1115, in the present-day departments of the Haute Marne and the Aube, respectively.

"St. Bernard (1091-1153), the fervent Abbot of Clairvaux, inspired the rapid expansion of Cistercian monasticism throughout Europe. Within sixty years after Cîteaux's humble beginnings, the Cistercian Order comprised more than three hundred and forty monasteries. The ascetic spirituality of the White Monks attracted adherents to the contemplative life from all strata of society, and the Order continued to grow in great numbers in the second half of the twelfth century and into the next. By the fifteenth century there were more than thirteen hundred Cistercian monasteries throughout Europe.''[3]

"The rules of enclosure restricted Cistercian nuns from taking part in the General Chapters at Cîteaux, although towards the end of the twelfth century some convents within a region held their own chapters, such as in Burgundy and in Castile. . . .[6]

The reproduction of the drawings for the important event of the General Chapter reaffirms the esteem for Roseman's oeuvre on the monastic life.

Abbots and abbesses, as well as priors and prioresses, of Trappist monasteries worldwide convene every three years for the General Chapter, which is now held in different locations. The OCSO General Chapter of 2011 was held in Assisi, from the 7th to the 28th of September.

The credit line reads: Dessin de Stanley Roseman.

The Abbey of Cîteaux - Birthplace of Cistercian Monasticism

"A stunning series of drawings depicting the monastic life in Europe."

- Associated Press, Rome

© Stanley Roseman

1. Louis J. Lekai, The Cistercians, (Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1977), pp. 11, 13.

2. Ibid., p. 250.

3. Ibid., pp. 42-46.

4. Charter of Charity from Lekai, p. 445.

5. C. H. Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism, (London and New York: Longman Group Ltd., 1984), p. 160.

6. Lekai, The Cistercians, p. 347-351. For the general chapter of nuns at Las Huelgas, see also Lina Eckenstein,

Woman under Monasticism, (New York: Russell & Russell, Inc., 1963), p. 191.

7. Lekai, The Cistercians, p. 30.

8. Ibid., pp. 312-315, 318, 319.

9. Ibid., p. 316.

10. Ibid., pp. 81-83.

2. Ibid., p. 250.

3. Ibid., pp. 42-46.

4. Charter of Charity from Lekai, p. 445.

5. C. H. Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism, (London and New York: Longman Group Ltd., 1984), p. 160.

6. Lekai, The Cistercians, p. 347-351. For the general chapter of nuns at Las Huelgas, see also Lina Eckenstein,

Woman under Monasticism, (New York: Russell & Russell, Inc., 1963), p. 191.

7. Lekai, The Cistercians, p. 30.

8. Ibid., pp. 312-315, 318, 319.

9. Ibid., p. 316.

10. Ibid., pp. 81-83.

Page 3 - Cistercians and Trappists

On the bottom of this page are links

to the other pages on the Monastic Orders.

On the bottom of this page are links

to the other pages on the Monastic Orders.

"The Cistercian Order takes its name from the Abbey of Cîteaux founded in Burgundy in 1098 by Robert of Molesme, who sought a contemplative life of asceticism and solitude inspired by the lives of the third- and fourth-century Christian eremites in the deserts of Egypt and Judaea. Abbot Robert and some twenty monks from Molesme, the monastery he had previously founded in 1075 in the diocese of Langres, resettled about twenty kilometers south of Dijon on a forested tract of land donated to them for the purpose of beginning a new monastery.[1] At a place called Cîteaux, in Latin Cistercium, the venturesome troop observed a monastic routine that was an alternative to the customs and elaborate ceremonial established at the great, Burgundian Abbey of Cluny, founded in 910, whose influence by the late eleventh century extended to more than a thousand affiliated monasteries in Europe.

Cistercian Economy

9. The Cistercian Abbey of Poblet, Tarragona, summer of 1979.

Cistercian monasticism constitutes a major part of Roseman's oeuvre on the monastic life. In researching and planning his work, the artist recounts, ". . . my thoughts were towards Europe, for monastic life is interwoven with the history and culture of Europe.'' Writing about his sojourns in the monasteries, the artist further recounts: "The second year of our travels to monasteries brought Ronald and me in June of 1979 to the Abbey of Cîteaux, the birthplace of Cistercian monasticism. We were very appreciative to have received a cordial letter of invitation from the Abbot of Cîteaux, Dom Loys, who writes to say: 'It is with pleasure that we shall receive you.' ''

Vineyards and Wine Making

"The Cistercian Order greatly advanced the socio-economic development of medieval Europe," writes Roseman in his text on monasticism. "Cistercians brought expert organization and management to the cultivation of the land on a large scale. Willingly accepting donations of barren and inhospitable terrain on which to build their monasteries, Cistercians cleared parts of woodland and forests for agricultural purposes and engaged in land reclamation that transformed dunes and swamps into fertile pastures. . . .[7]

"Farming, synonymous with manual labor from the early years of the Order, continues in monasteries today, as I observed, for example, at St. Sixtus Abbey, in Flanders, where in 1981 I drew Brother Dries scything the field."

7. Roseman drawing Brother Dries at St. Sixtus Abbey, Belgium, 1981.

8. Brother Estaban carrying feed to the Livestock, 1979

Abbey of San Pedro de Cardeña, Spain

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Switzerland

Abbey of San Pedro de Cardeña, Spain

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Switzerland

"With their corporate work force of lay brothers, or conversi, that is, the monks who carried out the greater share of the manual labor, Cistercians created a successful agrarian economy at a time when the feudal system was declining in efficiency. . . ."

A number of monks whom Roseman painted and drew were engaged in farm work, as was Brother Jan Bosco, who took care of the herd of beef cattle at St. Sixtus; Brother Petrus, who worked on the poultry farm at Westmalle, in the province of Antwerp; and Brother Samuel, who managed the dairy farm at the Abbey of La Trappe, in Normandy.

Scholarship and Study

900th Anniversary of the Founding of the Cistercian Order

1998 commemorated the 900th anniversary of the Cistercian Order. During that ninth centenary year, Roseman had the opportunity to include two additional monastic communities - one of Cistercian monks and the other of Trappist nuns - to the artist's extensive work on the monastic life.

© Stanley Roseman

© Photo Ronald Davis

Presented at the top of the page and here is the eloquent drawing A Cistercian Monk at Vespers, (fig. 11). The drawing of Brother Alberto, rendered in black and bistre chalks on gray paper, beautifully expresses contained movement of the figure and the piety of the monk bowing in prayer and reciting the Gloria Patri.

At the Trappist Abbey of Echourgnac in Aquitaine

Returning to the Abbey of La Trappe in Normandy

At the Cistercian Abbey of Chiaravalle Milanese

14. Portrait of Père Robert, 1998

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, France

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, France

13. Portrait of Soeur Monique, 1998

Abbaye d'Echourgnac, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, France

Abbaye d'Echourgnac, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, France

In the 900th anniversary year of the founding of the Cistercian Order, Roseman took up his paper and chalks to resume drawing at the Abbey of La Trappe, which gives its name to the branch of Cistercian monasticism familiarly called the Trappist Order. Roseman's long and creative association with La Trappe began in 1979.

Presented at the top of the page is the superb drawing Père Robert at Vigils, 1982, in the renowned collection of master drawings in the Albertina, Vienna.

In September 1998, Roseman and Davis were cordially invited to the Cistercian Abbey of Chiaravalle on the periphery of Milan. Chiaravalle was founded in 1135 as a result of St. Bernard's journey to Milan that same year and the enthusiasm of the Milanese to establish a Cistercian monastery. The name "Chiaravalle" derives from its motherhouse Clairvaux, of which St. Bernard was the Abbot.

"On Wednesday afternoon," Roseman writes, "Padre Gabriele thoughtfully gave Ronald and me a personal organ recital, which included works by Bach, Schumann, and Vivaldi. In the red-brick, beautiful abbey church that integrates the rounded arches of the Romanesque with early Piedmontese Gothic vaulting, Ronald and I sat enthralled listening to the memorable organ recital by the gifted musician and Cistercian monk.''

12. Portrait of Padre Gabriele, 1998

Abbey of Chiaravalle Milanese, Italy

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Switzerland

Abbey of Chiaravalle Milanese, Italy

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Switzerland

At the Trappist Abbey of San Pedro de Cardeña in Castile

In the summer of 1979, Roseman and Davis made their first journey to monasteries in Spain. The Trappist Abbey of San Pedro de Cardeña is secluded in a valley southeast of Burgos, in the province of Old Castile.

On the monastery farm, Roseman drew Brother Estaban carrying feed to the Livestock, (fig. 8). The excellent chalk drawing combines earth colors of red and light and dark bistre chalks on ochre paper, which imbues the composition with a feeling of a warm, Spanish summer's day.

Drawing with spontaneity in the use of the chalk medium, Roseman effectively depicts the forward motion of the Trappist monk wearing overalls, a shirt with sleeves rolled up, and a large straw hat as he trudges along carrying two buckets of feed to the livestock on the monastery farm. (See "Correspondence from the Monasteries," and "Monastic Journey Continued," Page 8 - "Monasteries in Old Castile.")

At the Cistercian Abbey of Poblet in Tarragona

The Cistercian Abbey of Santa Maria de Poblet, founded c.1151, is a majestic complex of Romanesque and early-Gothic architecture, with watchtowers rising above orchards and vineyards on the plains of Tarragona, as in the panoramic photograph, (fig. 9).

Abbot Mauro Estiva i Alsina, who was to be elected Abbot General of the Cistercian Order (1995-2010), graciously received Roseman and Davis, thoughtfully invited them to share in the daily life of the monastery, and was greatly encouraging to Roseman in his work on the monastic life - an encouragement deeply appreciated by the artist and his colleague.

St Benedict in Chapter 48 of his Rule prescribes that prayer be complemented by manual labor and sacred reading, lectio divina. Specific times of the monk's daily routine are allocated for reading and study.

Roseman writes: "The Cistercian monk and historian Louis J. Lekai states in relating the development of Cistercian monasticism that 'the figure of the Cistercian ascetic spending his day in prayer and hard manual labor was replaced by the scholarly monk, dividing his working hours between school and library.'[10] This tendency for scholarly pursuits came about in Paris in the mid-thirteenth century when the Cistercian Order opened the College of St. Bernard, the first house of study for monks attending university. . . . By the end of the century, Cistercian colleges had been established at Oxford, Montpellier, Toulouse, Würzburg, and Cologne.''

The beige drawing paper suggests the color of the stone walls and ceiling of the library; the space around the figure of Brother Pedro, the volume of the hall. The central placement of the figure on the page is complemented by a geometric leitmotif in the artist's rendering of shapes and forms. The black and white chalks establish the monk's habit of black scapular and white tunic. Here Roseman has created an engaging image of a Cistercian monk absorbed in reading and study.

© Photo Ronald Davis

10. Brother Pedro in the Library, 1979

Abbey of Poblet, Spain

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

Private collection, New York

Abbey of Poblet, Spain

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

Private collection, New York

"Abbot Stephen, a learned man and able administrator, fostered good relations with the local nobility; expanded the monastery estates; and engaged in research on Gregorian chant for singing the Psalms and Ambrosian hymns, which St. Benedict prescribes for the liturgy. Stephen Harding meticulously prepared a new edition of the Bible with the assistance of Jewish scholars to insure the accuracy of the translation of the Old Testament from Hebrew to Latin.[2]

In early November 1998, Roseman and Davis were graciously welcomed by Abbess Geneviève and the community of Trappist nuns at the Abbey of Echourgnac, Notre Dame de Bonne Espérance, located southwest of Périgueux in the historic region of Aquitaine. The artist and his colleague presented the nuns with a gift of a plant abundant with flowers, which the Community thoughtfully placed in church by the statue of Mary near the altar.

Roseman was invited to draw the nuns at the Divine Office and in private prayer in choir. He was also invited to draw in the fromagerie, for cheese production is a traditional work in Cistercian monasteries in France, and Echourgnac makes an assortment of delicious cheeses, a main source of the monastery's income.

Several nuns kindly sat for the artist so that he could include portraits in his series of drawings at the Abbey of Echourgnac. Presented here, (fig. 13), is a beautiful portrait drawing of Sister Monique.

"From the early centuries of Western monasticism," Roseman further relates, "monks cultivated vineyards for providing wine for the Eucharist, for medicinal purposes, and as a beverage to be consumed 'sparingly' at meals, as stipulated in Chapter 40 of the Rule of St. Benedict. Monasteries received gifts of land with vineyards, but more often the monks cleared woods or brambly slopes to plant grape vines. At Cîteaux by the end of the twelfth century, the monastery vineyards included the famous Clos de Vougeot, comprising about 125 acres from whose harvest Cîteaux produced, until the French Revolution, the most celebrated of Burgundy wines. . . .[9]

Cistercians were important producers of wine in Europe through the centuries, and today a number of Cistercian and Trappist monasteries continue to cultivate vineyards, as Roseman and Davis observed in Spain in the summer of 1979 when they sojourned at the Abbey of Poblet.

"Cistercians raised sheep and by the thirteenth century were the foremost producers of wool in England, Ireland, and Wales. . . . Cistercians established many of the largest fisheries in Europe, introduced methods of selective breeding, built dams, diverted waterways to increase the size of the local fish population, and created new aquatic habitats. . . . With advanced methods of gardening and transplanting crops from one region to another through the network of monastic affiliation, Cistercians made important contributions in horticulture, such as in the thirteenth century at the German Abbey of Doberan, where plant experimentation was carried out in a glass-roofed building, a precursor to the modern-day greenhouse.[8]

Page 4 - Trappists Continued presents a history of Trappist monasticism; a section on the Night Office, or Vigils; further selections of Roseman's work; and photographs of the artist and the monks, including Père Robert teaching Roseman Cistercian sign language in the tailor shop, where the artist drew the monk at work.

Page 3 - Cistercians and Trappists

Padre Gabriele is seen here in profile, (fig. 12), his fair complexion complemented by his black skullcap. Bold strokes of black and white chalks describe the monk's habit. With painterly use of the chalks and a vivid presence of the individual, this impressive work exemplifies Roseman's mastery of the art of portraiture.

Ribbon-like lines of bistre chalk accented by an oval contour of black chalk set off the nun's face, finely rendered with the blending of chalks on gray paper. The translucent quality of the skin tones are enhanced by silvery-white highlights and touches of red chalk in the warm shading. Roseman's compelling portrait of a middle-aged woman with a peaceful countenance attests to the Trappist's nun's dedication to the contemplative life.

''The pictures - splendid and telling all at once - form the stimulating vanguard

towards so original and deep a study of the monastic life.''

towards so original and deep a study of the monastic life.''

- ARA arte religioso actual, Madrid

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

Roseman and Davis took their meals with the monks in the refectory, an impressive vaulted hall built in the thirteenth century, and joined the community for the daily round of communal prayer. The artist's drawings from Poblet include depictions of monks at prayer and work (as seen on the page "Ora et Labora, Prayer and Work"), as well as at study, exemplified by the fine drawing Brother Pedro in the Library, (fig. 10, below).

At the Abbey of Poblet in the summer of 1979, Roseman drew Brother Pedro at study in the library. The young, dark-haired monk who befriended the artist and his colleague explained on a tour of the Abbey that the library, a large hall with slender pillars and pointed arches dating from the thirteenth century, had been the scriptorium and was transformed in the late seventeenth century for use as the library.

Père Robert, A Trappist Monk at Vigils

1982, Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

1982, Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

Fra Alberto, A Cistercian Monk at Vespers

1998, Abbey of Chiaravalle Milanese, Italy

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private Collection

1998, Abbey of Chiaravalle Milanese, Italy

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private Collection

11. Fra Alberto, A Cistercian Monk at Vespers, 1998 Abbey of Chiaravalle Milanese, Italy

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private Collection

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private Collection

Père Robert is the subject of an equally superb drawing in chalks on gray paper, from 1998, (fig. 14). The bespectacled, Trappist monk wears a thin moustache and a goatee, a rarity in the monastic world for monks are usually clean shaven or full-bearded. The artist's skillful rendering integrates calligraphic strokes and transparent and solid passages of black and bistre chalks that describe the monk's hood and skullcap complemented by fine, sculptural modeling of the face, in profile, with white heightening and warm shading. Roseman has created a deeply-felt portrait of his longtime friend as he meditates and prays.

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

© Stanley Roseman

Recounting his and Davis' days at Chiaravalle, Roseman speaks of the warm reception they received on their arrival on Monday, September 21st, and the tour of the Abbey by Padre Gabriele, the organist, with whom they shared a love of music and art. The monastery's frescos include a beautiful Madonna and Child by the Milanese Renaissance master Bernardino Luini, a pupil of Leonardo da Vinci.